(2025) for the Mixed-Reality Sound Installation (Artist: Chia-Wei Hsu)

Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), Taiwan, 2025/07/26 – 2025/09/28

Program Note

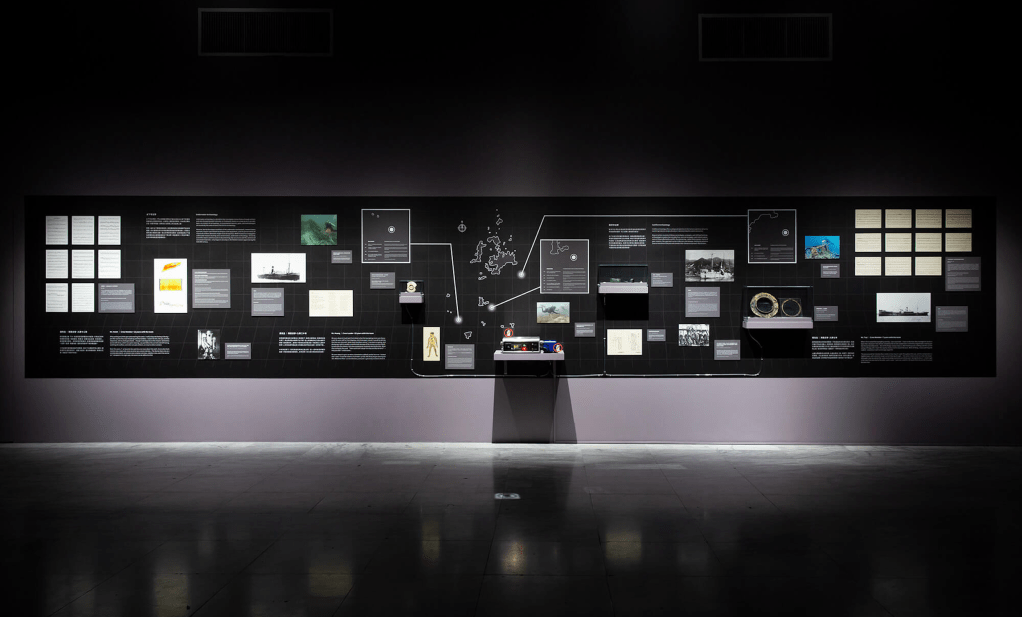

1. Underwater Soundscape Recording

The collection of underwater sounds was not merely an act of documentation but a way of re-sensing the environment and history. In this project, I regarded the seabed soundscape as a “living archive”: the crackling of shrimp, the choruses of fish, the abrasion of sand against metal, the tremor of raindrops striking the sea surface, even the distant reverberation of fishing boat engines. These sounds belong to nature yet also carry cultural and historical traces. The act of recording itself became a form of sonic shaping: the angle of the microphone, the depth of its placement, and the time of recording determined whether what emerged was the trace of labour, the breath of the environment, or the disappearance of time itself. Through continuous overnight recordings, the archive extended into timeframes beyond human presence, revealing nocturnal ecologies and the rhythms of the sea itself. Within the exhibition context, these sounds were further transformed into music, permeating the entire work and unfolding as contrapuntal layers alongside other sonic elements.

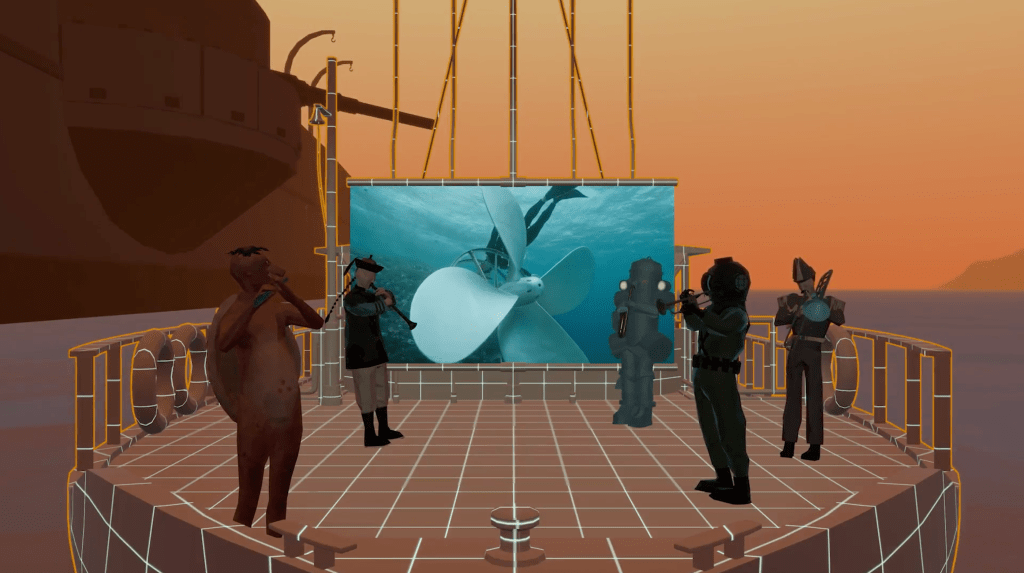

2. Score Recomposition and Re-voicing

The melodic materials in the exhibition were not simple reproductions, but rather gained new life through recomposition and revoicing. The Sea-going Song preserved much of its original shape in performance, but electronic textures derived from ocean recordings added harmonic layers and melodic lines, generating new resonances and spatial textures beyond its familiar folk contour. This approach both honoured the song as a cultural testimony of labouring memory and transported it into a contemporary sonic field, allowing it to “converse” across history and the present. In contrast, rediscovered military and colonial songs were not only re-scored through extended instrumental techniques and dissonant harmonies but also re-injected into the sea and re-recorded, allowing their sound to resonate with the marine environment. These operations symbolised the dissolution of their original authority, transforming them into fractured yet emotionally charged sonic residues. Through these processes of re-voicing and re-siting, songs of different origins became intersecting trajectories of memory, rather than static reproductions.

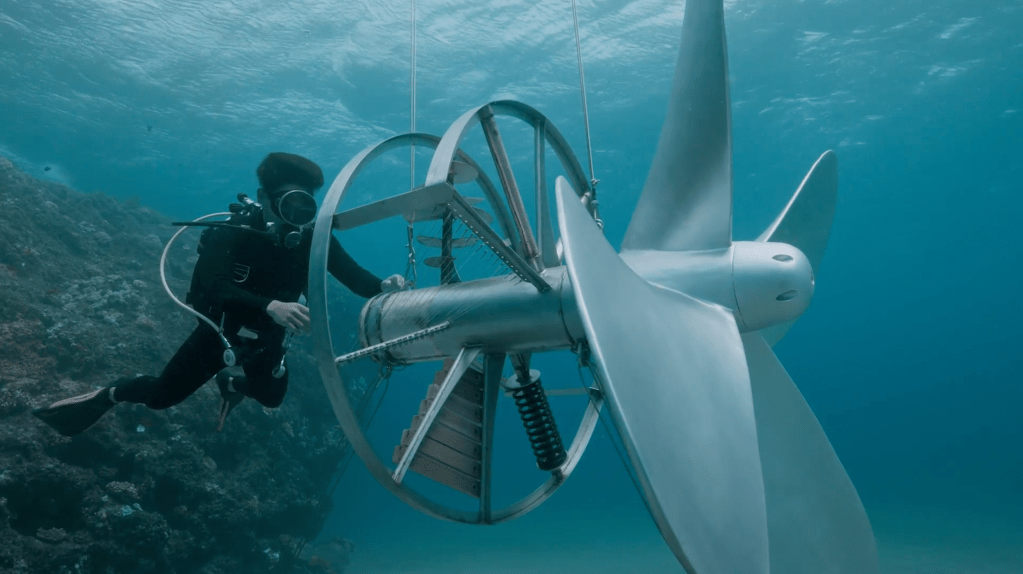

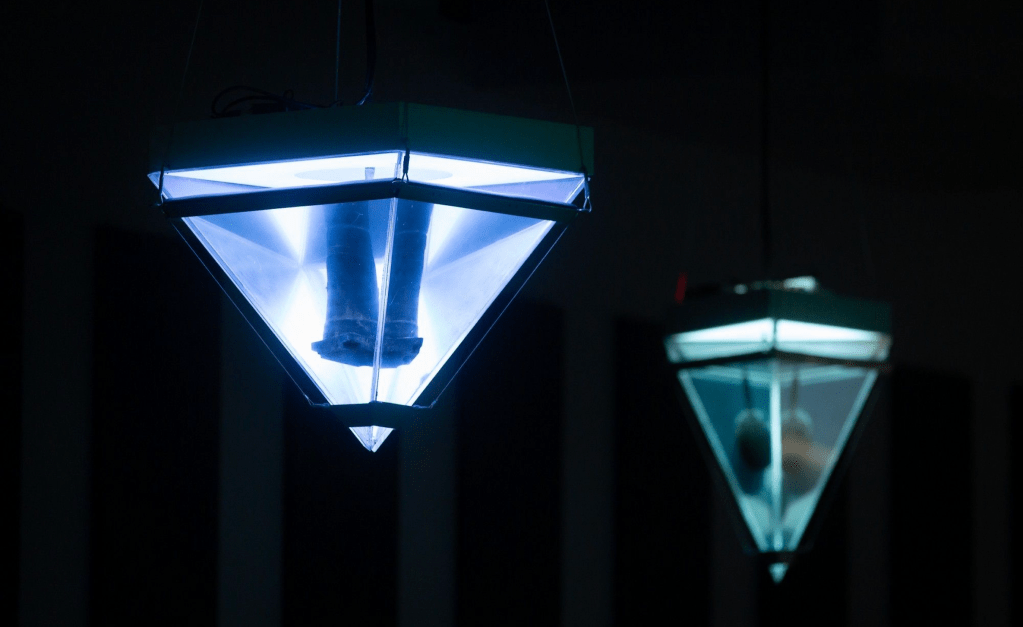

3. Underwater Performance and the Sonicity of Installation

The sounds of the underwater cello and percussion installation did not attempt to mimic terrestrial performance but instead emphasised the resistance, delay, and transformation unique to the aquatic medium. The bow’s movement through water density produced broken textures; the resonance of struck materials was compressed and spectrally altered by the fluid; and the diver’s breath and movement permeated the sonic field as indispensable elements. These were not incidental by-products of performance, but were designed as the core of the installation, turning the instruments themselves into “sonic architectures” that functioned simultaneously as performers and as resonant bodies. What audiences encountered on site was not a completed musical piece, but a process in which sound and environment continually shaped one another: the resistance of water defined sonic textures, the materiality of instruments amplified aquatic qualities, and performers and environment co-created a new performative form. In this way, the exhibition space itself became an “underwater sound theatre,” directly placing the audience at the centre of interaction between creation and environment.

一、水下聲景錄音

水下聲音的收集,不只是紀錄性的行為,而是一種重新感知環境與歷史的方式。在此專案中,我將海底聲景視為一種「活的檔案」:蝦類的爆裂聲、魚群的合唱、砂石與金屬摩擦的迴響、雨點敲擊海面的顫動、甚至遠方漁船引擎的迴盪,這些聲音既屬於自然,也蘊含了文化與時代的痕跡。錄音的選擇與取捨本身就是一種聲音塑形:麥克風的角度、擺放的深度、錄製的時段,都會決定觀眾聽見的是勞動的痕跡、環境的呼吸,抑或是時間本身的消逝。透過連續整夜不間斷的錄音,聲音檔案得以延展到人類不在場的時間範圍,呈現夜間生態與海洋自身的律動。在展覽的脈絡中,這些聲音被進一步轉化為音樂,滲透於整體作品之中,與其他聲音元素對位並構成複調。

二、樂譜改編與再聲化

展覽中的旋律材料並非單純重現,而是透過改編與再聲化獲得新的生命。〈討海歌〉在展演中保持了大部分原曲的形貌,但由海洋錄音所變化成的電音加入了額外的旋律線與和聲層次,使之在熟悉的民謠音型之外,生成新的音響紋理與空間感。這樣的處理既為了尊重歌曲作為勞動記憶的文化見證,又將其帶入當代的聲音場域,讓它能與歷史與現在「對話」。相較之下,再次被發現的軍歌與殖民時期的曲目,除了透過樂器延伸技巧與不協和和聲被改寫之外,還被重新「注入」海中並錄製,使其聲響與海水環境發生共鳴。這些操作象徵軍樂原本權威性消解,轉化為斷裂的聲音殘餘。這些再聲化與再場域化的過程,使不同來源的歌曲成為交錯的記憶聲軌,而不只是靜態的再現。

三、水下演奏與裝置的聲音性

水下大提琴與打擊裝置的聲響,並非企圖模仿陸地上的演奏,而是強調在水中產生的阻力、延遲與變形。琴弓在水的密度下摩擦,聲音變得斷裂;擊打器具的共鳴在流體中被壓縮並改變頻譜;潛水員的呼吸與移動則滲入聲響,成為不可或缺的一部分。這些元素不再僅是表演的副產品,而被設計為裝置的核心,使樂器本身成為「聲音建築」,同時既是演奏者,也是共鳴體。觀眾在現場所體驗的不是一段完成的樂曲,而是一個聲音與環境互相塑形的過程:水的阻力塑造聲音的質地,樂器的物質性放大了水的特質,演奏者與環境共同生成一種表演的形式。我們希望把展覽空間本身成為一個「水下聲響劇場」,把觀眾直接置於創作與環境互動的中心。

Artist:Chia-Wei Hsu|Composer & Sound Design: Tak-Cheung HUI